Quebec’s chief coroner says their report about Jimmy Sivuak Eliyassialuk, 22, an Inuk man who died while in police custody in Nunavik, sat for more than a year longer than it should have leaving his family in limbo on the specific details of his death.

“It was dropped by everyone in the office, and I tried to find the reason why but have been unable to,” said Chief Coroner Pascale Descary in a French language exclusive interview with APTN News.

In this case, the coroner’s report sat in limbo long after it could have been released and was only made available to the family and public more than three years after his death in 2017.

The coroner’s website describes the average wait time following the death of an individual as 11 to 15 months.

Descary said that a coroner report is allowed to be released to the public after Quebec prosecutors, known in Quebec as the DPCP, decide not to press charges.

DPCP – Quebec’s prosecution service

KPRF – Kativik Regional Police Force – the force that polices Nunavik’s 14 Inuit communities.

BEI – Bureau des enquêtes indépendantes – Authority that investigates police in Quebec.

In March of 2019 prosecutors found the Kativik Regional Police Force (KRPF) were not “criminally negligent” in Eliyassialuk’s death in a Puvirnituq jail cell, a small village 1,634 km north of Montreal in subarctic Quebec.

“Everyone made the same error that I made,” said Descary regarding the extraordinary long wait for the release of the report. “The deputy coroner, the quality assurance team, all thought that the decision of the DPCP had not been made. You [APTN News] brought this to my attention, with reason.”

After identifying concerns with how Eliyassialuk’s investigation was handled, APTN had made repeated requests to the Quebec coroner for their report of the incident.

Shortly after the prosecutors made their decision in 2019, APTN was told by a member of the coroner’s communications staff that, “the report should be available in the coming weeks.”

Follow up requests made in 2019 and 2020 received similar responses.

As a result, APTN filed an access to information request for the report as well as for the communications between coroner staff regarding Eliyassialuk’s report.

Many of the emails given to APTN were redacted and entire documents were withheld.

But some shed light on the process of the coroner, while others only served to create more questions about Jimmy Sivuak Eliyassialuk’s death in a jail cell.

Everyone Called him Sivuak

Louisa Eliyassialuk Surusilak pulls out a tablet and hits play on a video. It starts in a gymnasium, where the busy chatter of a crowd is competing with an announcer speaking in Inuktitut.

Suddenly Jimmy Eliyassialuk, who everyone calls Sivuak, emerges from the shadows of a black curtained off area.

He is dancing an Inuit style jig, all loose limbs and frenetic energy. The crowd whistles their appreciation.

Sivuak took first prize in the Puvirnituq Snow Festival that year.

Louisa lets out a soft “hmm” of appreciation while watching the video.

Watch Jimmy Sivuak Eliyassialuk dance a jig

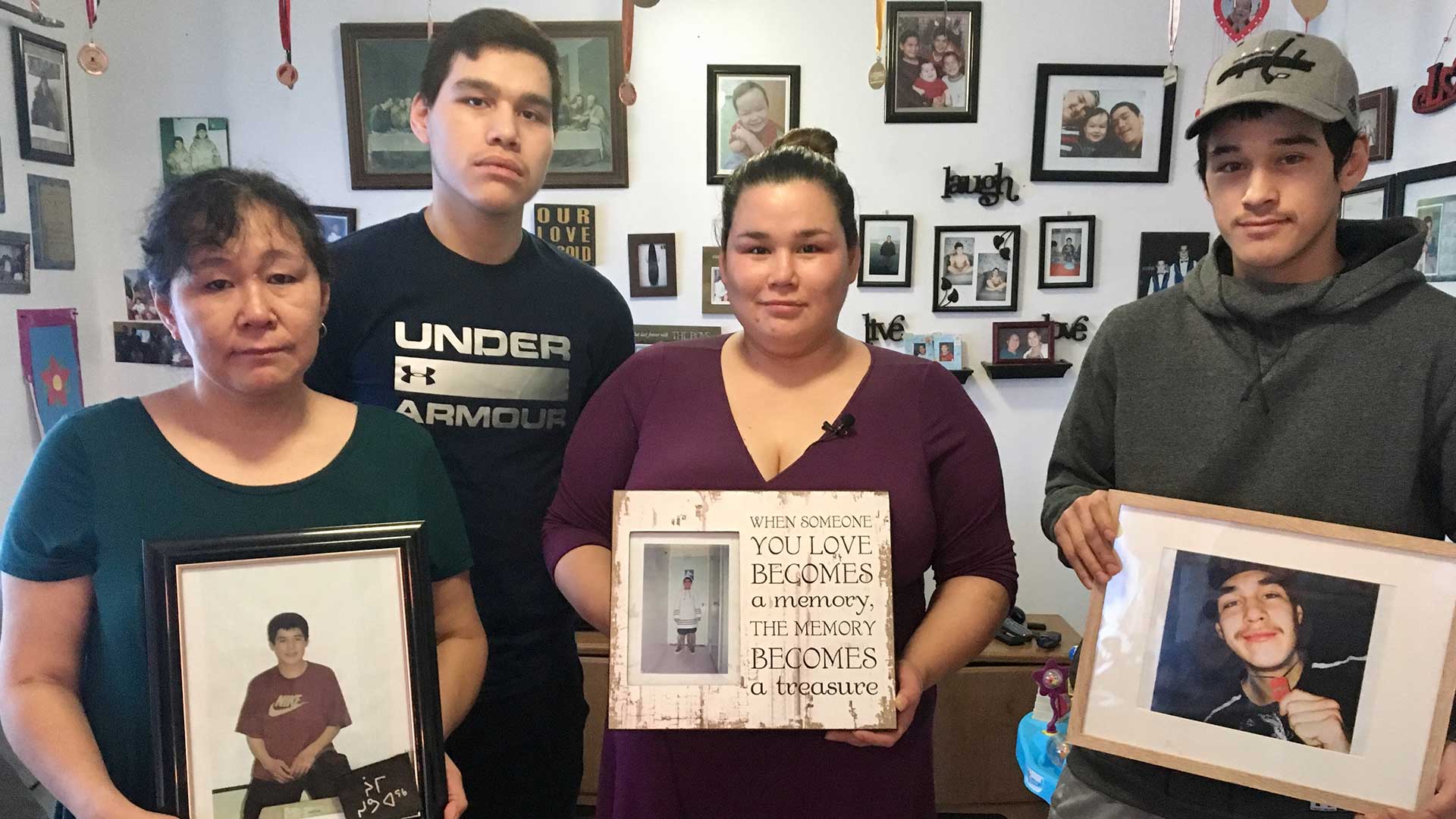

Images and videos like this are all she has left of her son.

“Eight hours, they didn’t notice him for so long. He was alone for eight hours. They just dumped him like garbage,” said Louisa though tears.

For more than three years Sivuak’s family has been searching for answers.

Louisa has found the process incredibly frustrating.

“We have asked for videos for when he got locked up, to see how long it took for them to see he was deceased, we were not given that information [the video], even though we were patiently asking, I asked, who was he with? Who saw him? But nothing,” explained Louisa in Inuktitut.

The Investigation

Using a mix of the coroner report and a Quebec prosecutor’s statement, APTN has pieced together Sivuak’s final hours.

On April 28, 2017, the KRPF, the force that polices Puvirnituq and 13 other communities in Nunavik, received a call at 9:20 a.m. from a man requesting help getting drunk people out of his home.

Two police officers arrived and took two inebriated men out of the house.

Police took one of them home. On the drive, Sivuak “appears to fall asleep” in the car.

“When he was too drunk why didn’t they bring him home or to the hospital?” asked Louisa back in November of 2018.

Instead the police took him to the Puvirnituq police station to sober up, an approach that “KRPF [Kativik Regional Police Force] officers often perform in such a situation.”

Sivuak was not under arrest.

At the police station, officers search Sivuak and placed him on his stomach in a cell.

Sivuak is still unconscious and in the eyes of the police, he seems to be sleeping.

He is left there for nearly eight hours, until a civilian guard informs police officers that Sivuak is not responding to the guard’s attempts to wake him.

When police arrive, they find that Sivuak hasn’t moved since they put him in the cell.

Officers’ attempts to resuscitate him fail.

At 5:47 p.m., Sivuak is pronounced dead after being moved to the Puvirnituq health centre.

The cause of death is later found to be alcohol poisoning. But according to the pathologist, foam was found in his trachea and bronchi meaning there is the possibility of “positional asphyxia” where the nose or the mouth is obstructed and prevents breathing.

The Follow Up

Because investigators are unable to determine when Sivuak died, the possibility of asphyxiation does not factor into the pathologist’s report.

Quebec prosecutors concluded that with regards to any charge of criminal negligence, there needs to be a clear “reckless disregard for respect for the life or safety of others” and that “the conduct must represent a marked and significant departure from the conduct of a reasonably prudent person.”

“There was no guard. No one was there,” said Sivuak’s sister Freddie in 2018 when APTN visited her at home in Puvirnituq.

She says the family was told that there was no one to replace the overnight guard when Sivuak was brought in around 9:30 a.m.

It’s unclear if a KRPF officer stayed behind to keep an eye on the jail from the time Sivuak was brought in until the evening shift guard arrived around 4 p.m.

“We have asked for videos for when he got incarcerated, to see how long it took for them to see he was deceased, we were not given that information, even though we were patiently asking,” said Sivuak’s mother Louisa.

“I didn’t know how to get information, we didn’t know who to go to get information. I don’t know why it takes long,” said Louisa through an Inuktitut translator in August.

Click here for a timeline of the investigation: Jimmy Sivuak Eliyassialuk

Despite having limited ability to understand English and no comprehension of French, in May of 2019 Louisa was able to request access to the police report, autopsy report, and toxicology report regarding Sivuak’s case.

All three of these reports go into the making of the coroner’s report.

It took the Quebec coroner over a year to respond to Louisa. In a letter written only in French, a language she doesn’t understand, they refused her request.

Wanting to see the documents is not enough said Descary – a person’s rights must be invoked.

“If a person says ‘I need these documents because we have a lawyer who needs them because we want to question the responsibility of whoever in the death of my loved one’, that could give an opening to a family.”

On March 18, 2019, days after prosecutors decide not to press charges, a flurry of emails were sent regarding Sivuak’s file.

The first is from Descary to the coroner in charge of Sivuak’s report, Steeve Poisson.

She notifies him of the prosecutors’ decision. Two and a half hours later, an administrator for the office asks Poisson, “A while ago you asked me to keep your report in the file in case of any twist, is it still appropriate to keep it in reserve?”

It is not stated what the “twist” is or why a report that was long ago deemed ready to submit to investigators and prosecutors would need further attention.

Poission’s reply, and many other parts of the emails obtained by APTN are redacted according to Quebec’s access to documents law, which says a public body may refuse to disclose the opinions and recommendations of its employees.

Months later in May 2019 is when the confusion over the prosecutor’s decision appears to begin.

The deputy chief coroner writes Poisson and says “…you have to wait for the BEI report and the decision of the DPCP before submitting” despite both of those events having already occurred. The BEI (Bureau des enquêtes indépendantes) is the police oversight body in Quebec.

A section of this email exchange is also redacted.

The final email exchange released to APTN is between a quality control agent and Poisson on Feb. 26, 2020.

In it, quality control informs Poisson that the file has been moved to “pending” status and that this new status “will no longer affect your [Poisson’s] statistics, this file may take longer to process.”

Poisson’s reply indicates he realizes that there’s been an error in communication regarding the status of the report.

“Here’s the press release, we thought you had it!” he writes.

The exchange ends when the quality control agent writes back: “Thanks, we’ll get back to you after we analyze the file.”

Nearly four months later on June 9 2020, APTN again inquiries about the abnormal delay in the release of Sivuak’s coroner report.

A spokesperson for the coroner says, “The investigation concerning the deceased is not finished.” This is fifteen months after the prosecutors have used the report to help determine not to lay charges in Sivuak’s case.

“A manifest error of communication, why no one saw that, it’s unfortunate,” Descary told APTN. “There are very minimal risks that such a thing would happen again.”

Descary said that a technician has recently been assigned to make sure that the communications between coroner staff and outside agencies flows smoother.

Descary also took the time to explain the importance of the role of the coroner.

“We work for life, for those who are left, for those who are alive. We want to protect the lives of other people by trying to understand the causes of unfortunate deaths that may have possibly been avoidable,” Descary said.

Aside from determining the circumstances of a violent death, the coroner has the power to make recommendations in the hopes of preventing similar fatalities.

Jimmy Sivuak Eliyassialuk’s coroner report had none.

Should the Investigation be Investigated?

Publicly, Quebec’s police watchdog, the BEI, had this to say regarding their investigation of Sivuak’s case.

“… the obligations of the police officers involved and the director of the police force involved provided for in the BEI Investigation by-law were met.”

But this 2019 statement contradicts BEI leadership.

In a 2018 personal letter obtained through an access to information request by human rights advocacy group La Ligue des Droits et Libertés, KRPF Police Chief Jean Pierre Larose is told by BEI Director Madeleine Giauque that Kativik police breached protocol regarding Sivuak’s investigation.

Giauque points out in the letter that one of the officers who put Sivuak in the jail cell was also assigned to work with the BEI on the case.

It was also found that officers discussed the case together before drafting their reports and speaking with BEI investigators.

Sivuak’s family also has good reason to question whether the Puvirnituq jail is safe.

In 2015, two years before Sivuak’s death, the Puvirnituq jail was the subject of a 2015 Quebec Bar Association report that called the jail conditions “third world”, as well as a 2016 Quebec Ombudsman report into justice in Nunavik.

The subject also came up 18 months after Sivuak’s death when KRPF Police Chief Jean Pierre Larose testified before the Quebec Inquiry into the Relationship between Indigenous People and Certain Public services.

Larose told the commissioner that they don’t have enough officers to patrol communities and staff the jails. Because they want to make sure they have enough officers on patrol, KRPF hires civilian guards, but that they’ve been having recruitment and retention issues.

“In some communities we do not have a lot of them,” said Larose.

If for whatever reason there is no civilian guard, Larose says that an officer is supposed to do it.

During the same testimony, inquiry lawyer Paul Crepeau invited Larose to look through hundreds of statements made to the commission about jail cells.

“We were told about cold water, abuse, insults, not giving drugs, not providing basic necessities for life,” said Crepeau “We’re talking about serious problems with guarding.”

Of the 142 calls to action the Quebec Inquiry released a year ago, several have to do with improving short falls in police funding and infrastructure. One call to action specifically mentions implementing all the recommendations made in the Quebec Ombudsmen report on justice in Nunavik, some which specifically mentioned the jail cell in Puvirnituq where Sivuak died.

Sivuak’s coroner report chooses not to reference these.

Request Denied

APTN’s request to speak with Steeve Poisson, the coroner who wrote the report for Sivuak’s case was refused.

Descary says she can’t question Poisson’s decision to not make recommendations.

“I understand why the family would have liked that recommendations had been made, I understand that, but what I can tell you, on the other hand, only eight per cent of our coroner reports have recommendations. It’s not that much,” said Descary.

Descary adds reports don’t have to have recommendations to make an impact, saying that reports contribute greatly to research.

“I’m satisfied with the impact that our reports have brought in general, those that have recommendations and those that have none.”

When asked about whether a coroner should take other investigations into account when deciding to make recommendations, Descary said they should, and that there is staff to help coroners with that.

Watch Tom’s two part series on Jimmy Sivuak Eliyassialuk

Here’s Part 1:

Here’s Part 2:

It is not known whether Poisson knew about the reports concerning Nunavik guards, jails, and concerns raised over the BEI investigation of the Kativik Regional Police Force.

“Coroners are based out of different regions, but may take on cases from other regions they may be less familiar with if they are available,” said Descary.

Poisson is based out of Mont-Laurier, 1,500 km south of Puvirnituq.

One call for action by the Quebec inquiry asks that liaison officers for public services be chosen by Indigenous authorities to work with the communities they serve.

The office of the coroner does not have a specific liaison officer, although Descary added that a coroner was hired last year who has 20 years of experience working in Indigenous communities for the federal government.

“We are very pleased to be able to count on her expertise, she does good work.”

After their interview with APTN News, the Coroner’s office announced the creation of a new committee called “Mortality in Indigenous and Inuit Communities”.

The Quebec Inquiry also makes several calls to action to better accommodate Indigenous language speakers when it comes to public services.

During her interview, Descary committed to have an English speaker call the family of Sivuak to better explain why their request for the reports into Sivuak’s death were denied.

Another death in custody

Back in Puvirnituq, Sivuak’s sister Freddie is adamant that she wants to see the video from the jail cell with her own eyes in order to know exactly what happened, or didn’t happen, from that time Sivuak entered the jail cell until someone found his cold body nearly eight hours later.

“We have the right to know,” said Freddie back in November 2018.

“Every day I think of him, how he died,” Louisa Surusilak added in a written statement.

“They took too long to find out he was dead.”

Meanwhile, 180 km to the south in the community of Inukjuak, the BEI is working on a new case.

On August 28, a 45 year old man was found dead in a KRPF jail cell.

The investigation is ongoing.